Life and death of Hirohito

Life and death of Hirohito, the facts

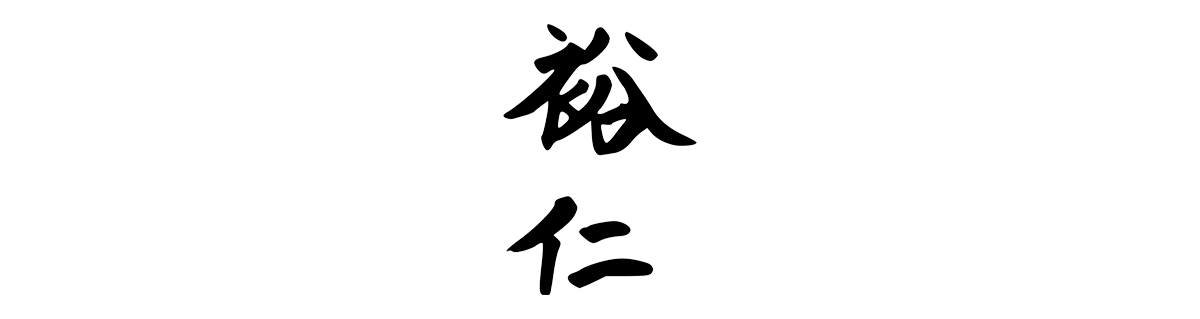

Hirohito, officially named Emperor Showa or the Showa Emperor after his death, was the 124th Emperor of Japan according to the traditional order. He reigned from December 25, 1926 until his death in 1989. Although he is better known outside Japan by his personal name Hirohito, in Japan he is now referred to only by his posthumous name Emperor Showa. The word Showa is the name of the era that corresponded to the reign of the emperor.

Begining

At the beginning of his rule, Japan was already one of the great powers - the seventh largest economy in the world, the third largest naval power and one of the five permanent members of the Council of the League of Nations. He was the head of state under the restriction of the Meiji Constitution during Japan's imperial expansion, militarization and involvement in World War II. After the war, he was not prosecuted for war crimes like others. During the post-war period, Hirohito became a symbol of the new state.

In the 1920s, as Prince, he visited Western Europe, including Belgium and the Netherlands. He ruled in the name of his father Yoshihito from 1921. Hirohito became emperor after his death in 1926. He formally led his country in the wars against China and in the Pacific.

Marriage

In 1924 Hirohito married Empress Kōjun (Princess Nagako of Kuni: 1903-2000) who was given the title of princess and with whom he had seven children. In 1933 their eldest son and heir apparent Akihito was born.

World War 2

In July 1939, the Emperor quarrelled with his brother, Prince Chichibu, over whether to support the Anti-Comintern Pact, and reprimanded the army minister, Seishirō Itagaki. But after the success of the Wehrmacht in Europe, the Emperor consented to the alliance. On 27 September 1940, ostensibly under Hirohito's leadership, Japan became a contracting partner of the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy forming the Axis Powers. The objectives to be obtained were clearly defined: a free hand to continue with the conquest of China and Southeast Asia, no increase in US or British military forces in the region, and cooperation by the West "in the acquisition of goods needed by our Empire."

Going to war

On 8 December (7 December in Hawaii), 1941, Japanese forces struck at the Hong Kong Garrison, the US Fleet in Pearl Harbor and in the Philippines and began the invasion of Malaya. With the nation fully committed to the war, the Emperor took a keen interest in military progress and sought to boost morale. According to Akira Yamada and Akira Fujiwara, the Emperor made major interventions in some military operations. For example, he pressed Sugiyama four times, on 13 and 21 January and 9 and 26 February, to increase troop strength and launch an attack on Bataan. On 9 February 19 March, and 29 May, the Emperor ordered the Army Chief of staff to examine the possibilities for an attack on Chungking in China, which led to Operation Gogo.

As the tide of war began to turn against Japan (around late 1942 and early 1943), the flow of information to the palace gradually began to bear less and less relation to reality, while others suggest that the Emperor worked closely with Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, continued to be well and accurately briefed by the military, and knew Japan's military position precisely right up to the point of surrender.

In the first six months of war, all the major engagements had been victories. Japanese advances were stopped in the summer of 1942 with the battle of Midway and the landing of the American forces on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in August. The emperor played an increasingly influential role in the war; in eleven major episodes he was deeply involved in supervising the actual conduct of war operations. Hirohito pressured the High Command to order an early attack on the Philippines in 1941–42, including the fortified Bataan peninsula. He secured the deployment of army air power in the Guadalcanal campaign. Following Japan's withdrawal from Guadalcanal he demanded a new offensive in New Guinea, which was duly carried out but failed badly. Unhappy with the navy's conduct of the war, he criticized its withdrawal from the central Solomon Islands and demanded naval battles against the Americans for the losses they had inflicted in the Aleutians. The battles were disasters. Finally, it was at his insistence that plans were drafted for the recapture of Saipan and, later, for an offensive in the Battle of Okinawa. With the Army and Navy bitterly feuding, he settled disputes over the allocation of resources. He helped plan military offenses.

The media, under tight government control, repeatedly portrayed him as lifting the popular morale even as the Japanese cities came under heavy air attack in 1944 - 45 and food and housing shortages mounted. Japanese retreats and defeats were celebrated by the media as successes that portended "Certain Victory." Only gradually did it become apparent to the Japanese people that the situation was very grim due to growing shortages of food, medicine, and fuel as U.S submarines began wiping out Japanese shipping. Starting in mid 1944, American raids on the major cities of Japan made a mockery of the unending tales of victory. Later that year, with the downfall of Tojo's government, two other prime ministers were appointed to continue the war effort, Kuniaki Koiso and Kantarō Suzuki each with the formal approval of the Emperor. Both were unsuccessful and Japan was nearing disaster.

Japan surrenders

On August 15, 1945, shortly after the US atomic bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet Union's declaration of war on Japan, Hirohito announced Japan's surrender to the Allies in a radio address to the Japanese people - the Gyokuon-hōsō.

Until WW2, Hirohito had the status of divine ikegami, Japanese for living kami, one of the most important concepts in Shintoism. In 1946 the Americans forced him to reject his divine status in a radio speech. From then on he was only the symbolic head of the Japanese state and of the unity of the nation.

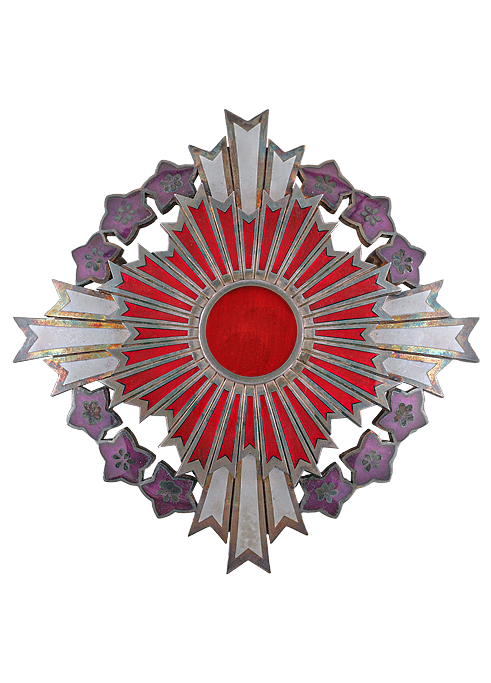

The Emperor not only lost all his powers through the intervention of the American ruler of Japan, General Douglas MacArthur; he also lost his vast lands and domains. However, the lavish lifestyle of the court did not change and the role of the emperor and his brothers in the wars was not officially investigated. Hirohito was a Knight of the Order of the Garter since 1929. In 1941 he was removed from this order. The Imperial ensign and its helmet were removed from the chapel of Saint George in Windsor Castle. After the Second World War, on the occasion of the Imperial state visit to the United Kingdom, these decorations were replaced. Hirohito was reinstated as a member in 1971.

In the early years after World War II, the court made a few half-hearted attempts to introduce the former God-Emperor to the Japanese people. Hirohito's unworldliness and shyness made that unsuccessful and Hirohito withdrew from public life. From then on the outside world saw only a neat-looking, small, waving man in a stiff tailcoat behind the window of a limousine or on a far and high balcony.

Japanese oppression

For some Dutch people he is the symbol of the cruel Japanese oppression (jap camps) in the Dutch East Indies. His visit to the Netherlands in 1971 was accompanied by fierce protests from Wim Kan, among others. To others, Hirohito was just, to the extent that he could, an opponent of war and violence. He is said to have exceeded his powers by speaking out against the occupation of Manchukuo (1931) and to persuade his country to capitulate at the end of World War II (1945). Historians disproved this image. They convincingly showed that Hirohito was well informed, co-determined policy and gave direct orders to army commanders and admirals. His support proved indispensable for military operations in China and the war in the Pacific. By subsequently regretting the past without pronouncing a guilty plea, he symbolized 'national repression'. In speeches during his controversial and riot-marked state visits to the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, the emperor expressed his regret about the war and what happened in it in a diplomatic and typical Japanese formal style.

Accountability for Japanese war crimes

The issue of Emperor Hirohito's war responsibility is contested. During the war, the Allies frequently depicted Hirohito to equate with Hitler and Mussolini as the three Axis dictators. After the war, since the U.S. thought that the retention of the emperor would help establish a peaceful allied occupation regime in Japan, and help the U.S. achieve their postwar objectives, they depicted Hirohito as a "powerless figurehead" without any implication in wartime policies. The emperor kept himself perfectly informed of war developments. Under his leadership, Japanese troops occupied large parts of Southeast Asia.

Death

On 22 September 1987, the Emperor underwent surgery on his pancreas after having digestive problems for several months. The doctors discovered that he had duodenal cancer. The Emperor appeared to be making a full recovery for several months after the surgery. About a year later, however, on 19 September 1988, he collapsed in his palace, and his health worsened over the next several months as he suffered from continuous internal bleeding. The Emperor died at 6:33 AM on 7 January 1989 at the age of 87. The announcement from the grand steward of Japan's Imperial Household Agency, Shoichi Fujimori, revealed details about his cancer for the first time. Hirohito was survived by his wife, his five surviving children, ten grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.

At the time of his death he was both the longest-lived and longest-reigning historical Japanese emperor, as well as the longest-reigning monarch in the world at that time. The latter distinction passed to king Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand when he surpassed him in July 2008 until his own death on 13 October 2016. The Emperor was succeeded by his son, Akihito, whose enthronement ceremony was held on 12 November 1990.

The Emperor's death ended the Shōwa era. On the same day a new era began: the Heisei era, effective at midnight the following day. From 7 January until 31 January, the Emperor's formal appellation was "Departed Emperor." His definitive posthumous name, Shōwa Tennō, was determined on 13 January and formally released on 31 January by Toshiki Kaifu, the prime minister.

On 24 February, the Emperor's state funeral was held, and unlike that of his predecessor, it was formal but not conducted in a strictly Shinto manner. A large number of world leaders attended the funeral. Hirohito is buried in the Musashi Imperial Graveyard in Hachiōji, alongside his father, Emperor Taishō.

-

Born: April 29, 1901

-

Tōgū Palace, Aoyama, Tokyo, Empire of Japan

-

Died: January 7, 1989

-

Fukiage Palace, Tokyo, Japan