Duration of this batte: 16 December 1944 - 25 January 1945

Battle of the Ardennes

Commanders of the Battle of the Ardennes

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Gerd von Rundstedt

George S. Patton Jr.

Joachim Peiper

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Battle of the Bulge, was the last major offensive by the German Wehrmacht on the Western Front in World War II. The battle took place in the Ardennes, from December 16, 1944 to January 25, 1945, and was won by the Allies. In the English-speaking world, this battle is known as the Battle of the Bulge, because the front line was shaped like a bulge or pocket.

In the summer of 1944, Germany had suffered severe defeats in which an important part of the German army was destroyed. After that, however, the fronts were temporarily stabilized so that an armored reserve could be built up again. Adolf Hitler now wanted to deploy those tanks with his last reserves of men for a major counter-offensive with which he hoped to settle the battle in his favor. Such a decision could only fall in the west, because on the eastern front, the depths of the Soviet Union would easily absorb any attack. To the west, however, it seemed possible to recapture Antwerp, the only major port with which the Allies could bring supplies. Within six days, two panzer armies, with many units of the Waffen-SS, had to break through the weakly occupied Ardennes with American troops, cross the Meuse and reach Antwerp. This would immediately surround the British Army so that it could be destroyed, a possibly fatal blow to the war effort of the Western Allies.

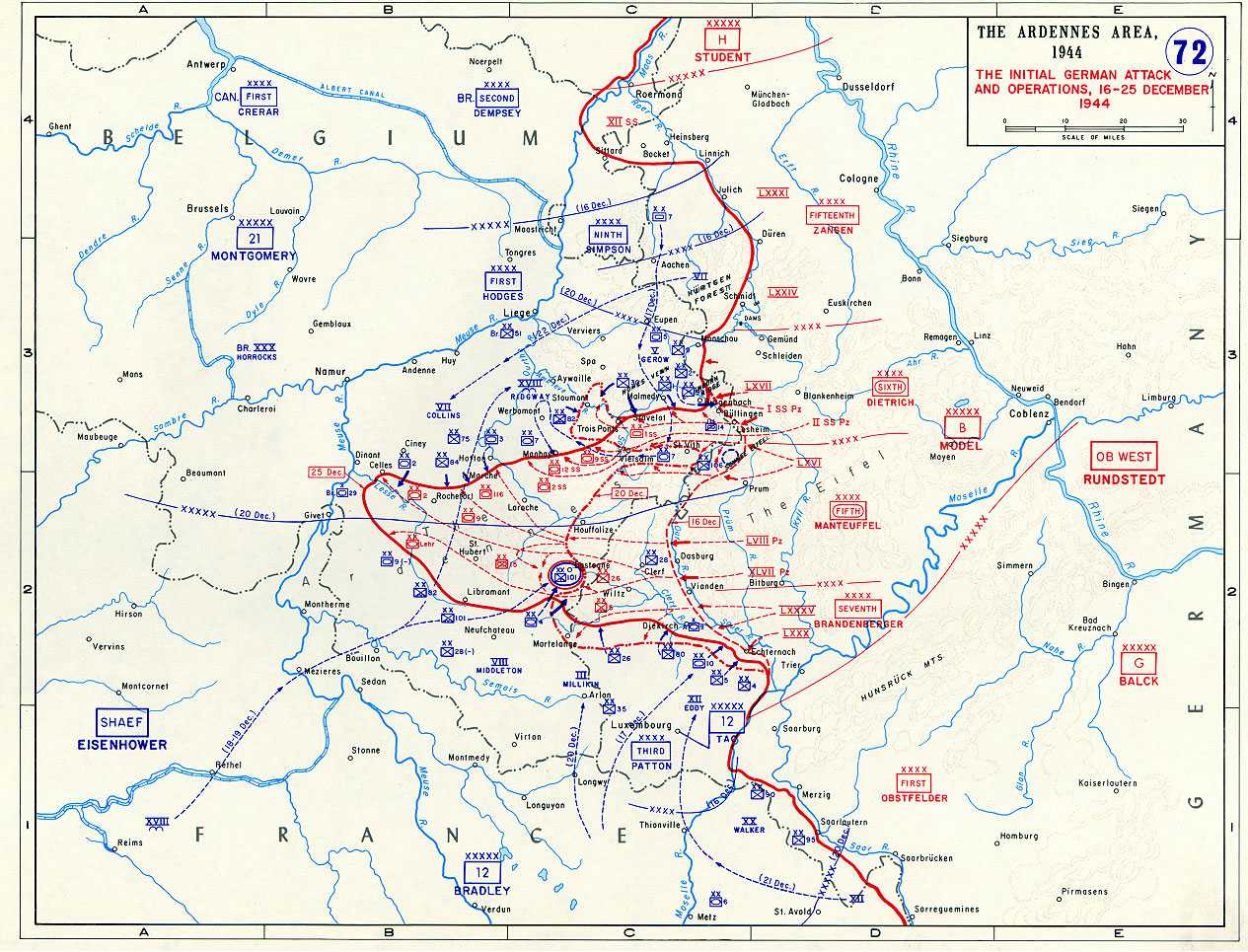

The offensive started on December 16. Bad weather provided cover for the German troops against the allied air force. However, it also made the roads of the Ardennes virtually impassable. The Northern 6th Panzer Army managed to break through and advance some thirty kilometers but failed to widen the breakthrough point to the north as American forces held out on the ridge of Elsenborn. Eventually they got stuck because of this and they could not reach Liège - where the Maas had to be crossed. To the south, the 5th Panzer Army was more successful. The breakthrough left a wide gap in the American front and the Germans continued to advance west for a week, reaching the Meuse almost east of Dinant. At that time, however, the American 101st Airborne Division had already driven to the Bastogne road junction and had set it up strongly for defense. The surrounded Americans held the town against all attacks and thus disrupted the German supply. Due to a lack of fuel and ammunition, the German tanks had to cease their advance near Celles on December 25.

American command in the north of the Ardennes had gone south. British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery took over command, built a close-knit front and posted British troops across the German advance route at Dinant. At the same time, American General George Patton from the south came to the rescue with the 3rd Army and relieved Bastogne. The weather grew sunnier and fighter-bombers ravaged the German troops. American armored divisions pouring in from all fronts created a great allied superiority of tanks. However, Hitler did not want to admit that the offensive had failed and ordered Bastogne after all. After a hard fight that failed. Montgomery attacked the German attack wedge from the north, and Patton from the south. Hitler now allowed to evacuate the Ardennes and around January 25 the Germans were back to their starting positions.

The offensive sparked tensions between the British and the Americans. The planned Allied attacks on the Rhineland were delayed for six weeks. Both Germans and Americans suffered heavy losses of tanks and men. However, the Americans had virtually inexhaustible reserves of equipment. The Germans, on the other hand, now had no more armor reserve to deal with the major offensive by the Red Army that broke out on the Weichsel on 12 January 1945. At the end of January, the Soviet armies stood before Berlin.

S.H.A.E.F.

German Wehrmacht

Battle specifications

Date of the battle

Duration of the battle

Reason for the battle

Location

Battle result

The plan

The Battle of the Bulge was Adolf Hitler's personal plan to cut off the northernmost Allied forces on the Western Front and then destroy them. Ever since the summer months of 1944, when Germany suffered catastrophic defeats in Normandy and Belarus, he had been thinking about launching one more massive, successful offensive. He considered a military victory necessary to keep alive the hope of final victory and to force the Allies, who had been demanding an unconditional surrender since early 1943, to negotiate an end to the war.

At the beginning of September the Allies had liberated Antwerp by a rapid advance, which provided them for the first time with a large port to resupply. Already on September 6, Hitler ordered a major counter-attack to be prepared to recapture Antwerp. On September 16, Hitler first discussed concrete options with his military staff. After Hitler learned about the situation in the west from Gerd von Rundstedt, he decided to go deeper into his plans on September 25. The situation on the Eastern Front did not seem to offer any chance of decisive success for a deployment of large reserves. In the west, however, there were indeed opportunities because the number of Allied divisions was much lower and they had a limited strategic depth to withdraw.

There are several reasons why Hitler chose the Ardennes as the area of operations. Probably the fact that he had achieved his first spectacular success on the Western Front in May 1940 was one of them. Then he had approved a daring plan, Fall Gelb, later called the Sichelschnitt, whose successful execution had previously seemed impossible. Afterwards, Hitler became convinced that he had devised the plan himself instead of one of his best strategists, Erich von Manstein. However, the situation and the balance of forces were completely different then from 1944. In 1940 he was able to concentrate half of his army in this area, in 1944 he had to fight on many fronts simultaneously. In 1940 the Luftwaffe controlled the airspace, but now the Allies. Bad weather could provide cover against this, but would also make the bad road network of the Ardennes almost impenetrable. During Fall Gelb, the Belgians and French had immediately evacuated the Ardennes; now there was a front that had to be broken. Hitler, however, wanted to exploit the fact that the Allies in the north had a stronger attack wing, while their southern wing in the Ardennes sector was only moderately occupied. With the destruction of twenty to thirty Allied divisions of the total of 62 divisions on the Western Front, the battle in the west would have to be decided in Germany's favor at once. He wanted to deploy 45 divisions for this.

The operation could only be called a success if the other positions on the western front, including those in the Netherlands, could be held and the Western Scheldt could be closed off. The situation on the eastern front had to be stable, so that the forces of the strategic reserve did not have to be called upon there. There had to be certainty that the reserves of men were available for the Western Front for the duration of the operation. Most importantly, however, the leading combat units would quickly defeat the opponent at the front, so that the enemy would not have time to stop the offensive with reserves. This could be done if the attack wedge had to travel a relatively short distance before reaching the main target. On October 9, Alfred Jodl put all attack options side by side one more time. The different options were presented as five operation plans:

- Operation Netherlands. This option involved a frontal attack to crush the British army. The attack was to be launched from the Venlo sector in a westerly direction towards Antwerp.

- Operation Liège-Aachen. The purpose of this attack was to roll up a long stretch of the American front. A main attack would be directed northwest from the northern tip of Luxembourg. The attack then had to swing north to coincide with a side attack launched in that direction from the area northwest of Aachen.

- Operation Luxembourg. Its purpose was the destruction of the US Third Army. Two assault spikes from central Luxembourg and the Metz sector were to meet in the Longwy sector and occupy the Minette area.

- Operation Lorraine. Two attack wings had to advance from Metz and Baccarat, which are places west of the Vosges, with the aim of converging at Nancy.

- Operation Alsace. Two attacks from the area east of Épinal and Montbéliard with the aim of converging near Vesoul.

After the military staff had weighed up the pros and cons of the various operation plans, the emphasis shifted more and more to variants 1 and 2. A breakthrough through the Ardennes would be combined with a march towards Antwerp. On October 22, Hitler gave the chiefs of staff of Oberbefehl West and of Army Group B, Siegfried Westphal and Hans Krebs, the opportunity to come and see and familiarize themselves with the plan. He made the plan clear to the generals and declared that Germany should finally launch an offensive in view of the war situation. Once upon a time, that 'eternal defense' had to be over. The offensive would consist of two phases. In the first phase it was a matter of reaching the Maas and forming a bridgehead. This phase had to be completed on the fourth day. In the second phase, the city of Antwerp was to be taken, on the sixth day. The aim of the operation was to cut off and destroy the Allied forces north of the Bastogne-Brussels-Antwerp line. At least as important was the elimination of the port of Antwerp, because that port was regarded as an important supply port for the Allied troops.

After going through all the attack plans, Hitler named November 25 as the day of the attack. At Heeresgruppe B headquarters and at Oberbefehl West, Von Rundstedt and Model immediately expressed their objections to the design of the operation. They therefore came up with alternative proposals.

From Fall Weihnachtsrose to the Battle of the Bulge

Originally, the attack would be called Fall Weihnachtsrose. Later Adolf Hitler had the name changed to Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein. The original name was based on the fact that the attack was to take place around Christmas. The new name was intended to be a misguidance as it suggested a defensive position. The name would not become popular after the war and was rarely used to indicate the offensive, also because Hitler came up with another new designation two days before the offensive: Herbstnebel. Already during the final phase of the battle, the Western press came up with the designation Battle of the Bulge. That referred to the salient or front arch that was seen as a "bulge". After the war in Germany they spoke of the Ardennes Offensive and in the Netherlands this was adopted as the "Ardennes Offensive". In French it became La bataille des Ardennes, the "Battle of the Bulge".

The offensive

At around 05:30 on December 16, a half-hour barrage of two thousand German guns broke loose on the American positions between Monschau and Echternach. V-1s, on their way to Liège and Antwerp, simultaneously roared a fiery trail through the dark sky. The 6th Panzer Army attacked at 06:00. The last major German offensive of the Second World War had begun.

Through the dense fog, fourteen German divisions advanced from the woods of the Snow Eifel to the sparsely manned American lines between Monschau and Echternach. Omar Bradley, commander of the 12th Army Group, at that time had 31 divisions on Germany's western border. Sixteen of these divisions were located north of the Ardennes between Geilenkirchen and Monschau. Ten divisions faced the Saar, south of the Ardennes. Only five divisions were stationed along the approximately two hundred kilometers long front in the Ardennes.

No action had taken place in the Ardennes since September. The Americans had therefore moved their best troops from the area to places where fighting was fierce, and had mainly deployed inexperienced or weakened troops in the Ardennes. Such as the 106th Infantry Division, which had only four days of combat experience, and the 4th and 28th Infantry Divisions, both of which had suffered heavy losses in the Battle of Hurtgen Forest and were in need of a rest period. On the front of these three divisions, the Germans concentrated the fiercest attack force.

At first, the Americans were completely taken by surprise. The Germans launched an artillery bombardment, while the troops soon advanced towards their designated sectors. The American outposts only realized the significance of the artillery bombardment when the first German troops emerged from the fog. The weather was exactly as Hitler wanted it to be. A low cloud cover completely hid the German troop movements from aerial observation. Allied air forces remained grounded powerless. Nevertheless, the German advance did not proceed as quickly as hoped. In view of the limited number of tanks available, Hitler had ordered that the front should only be broken by the infantry. That breakthrough then had to be exploited by the panzer troops. The poorly trained people's grenadiers turned out not to be so effective in this. Thus, the first delays already occurred. The muddy terrain proved almost impassable for heavy vehicles.

Only in the northern and southern sectors of the front did the attackers encounter considerable resistance. Between Bütgenbach and Monschau, where the 6th Panzer Army was located with two panzer divisions and four infantry divisions, the battle-ready American 5th Corps of Gerow had established itself, preparing an attack on the Roerdal Dam. When the Americans saw the Germans approaching, they took up defensive positions and tried to stop the enemy. On this part of the front, the Germans ran against an immovable wall on the ridge at Elsenborn. Here the Americans made optimal use of one of their strongest points: a heavy corps artillery with central fire control. Fire from large numbers of 155mm M59 'Long Tom's could be quickly diverted to any German infantry concentration. Imminent breakthroughs were always stopped. The holding out of the "shoulder" at Elsenborn was a big setback for the Germans because there was no room to deploy for an attack at Liège. The entire Panzer Army got caught up in a huge traffic jam. An exception was the special Kampfgruppe Peiper who had the assignment to find a route to the Maas a little further south than Elsenborn as an armored striker and to capture an intact bridge. This battle group, the SS Panzer Abteilung. Including 501, equipped with the heavy Tiger II (Königstiger), it would ultimately achieve the deepest penetration in this sector.

Also in the south, the four infantry divisions of the German 7th Army failed to break through the US 4th Infantry Division. In contrast, in the middle sector, where the 5th Panzer Army operated with three panzer divisions and four infantry divisions, the front broke wide open. Along the Our, the American 28th Infantry Division, which had to defend a front of sixty kilometers, was rolled up without much effort by five German divisions. Two regiments of the inexperienced 106th Division were surrounded in the Snow Eifel. The Americans held out on their front lines for three days, expecting their armored reserves to break through the encirclement. When help failed to materialize and ammunition ran out, their officers decided to surrender the units at once instead of breaking out west. This decision was later heavily criticized as it represented the greatest American surrender ever to the European combat arena. More than 6.000 men were taken captive.

Confusion

The confusion behind the front was great. In the first hours of the offensive, Allied headquarters initially did not realize the gravity of the situation. The reports from the front were vague, confused and often contradicted. The purpose of the Germans was not clear to anyone. It was hard to believe that Hitler had really launched a massive offensive with Antwerp as its target. It was therefore thought to be a disruptive attack aimed at disrupting the forthcoming offensive against the Saar led by Patton. As a result, the situation was underestimated by the Americans, with the result that reserves were deployed too late. It was not until late in the afternoon that Eisenhower gave the order to General Omar Bradley, commander of the 12th Army Group, that two armored divisions - the 7th of the 9th Army in the north and the 10th of the 3rd Army south of the Ardennes - should join the 8th Corps. help had to come.

The lack of information was partly due to German saboteurs under Otto Skorzeny, who had infiltrated in American uniforms and jeeps the night before the attack and cut many telephone lines behind the front. [15] The original plan of Skorzeny's Trojan Horse group, Operation Greif, aimed with the independent 150th Armored Brigade, equipped with previously captured American armored vehicles and five Panther tanks disguised as M10 tank hunters, to obtain fuel supplies behind the lines and bridges across the Meuse. to occupy. This plan could not be carried out because Dietrich's tanks were stopped by the US 5th Corps to the north. Ultimately, the 150th PB was used for regular attacks. Seven or eight jeeps with saboteurs, who could have infiltrated anyway, did manage to add significantly to the confusion behind the American front. The wildest rumors circulated about "thousands of saboteurs disguised as Americans." The strict security measures that the Americans now felt they had to implement only added to the chaos and delayed the advance of reserves to the battlefield. Even at the Allied headquarters at Versailles, security was tightened because it had been learned that Skorzeny's men were planning to kill Eisenhower. An Eisenhower-like Colonel was being driven back and forth like bait. There was also a rumor that a saboteur disguised as a general was walking around to create confusion. This was not correct, but this added to the confusion behind the front. Everyone had to constantly answer questions like "Who is Betty Grable's new man?", "What league does that baseball team play in?" and "What's Donald Duck's girlfriend?" Not even generals escaped this. The saboteurs were all quickly caught and most were executed.

When 1.200 German paratroopers landed behind the front on the night of 16-17 December, the confusion and panic intensified. That was almost all that the Germans managed to achieve with this parachute action, Operation Stößer, because it was not a success. Originally it was intended that the paratroopers, under the command of Colonel Baron Friedrich August von der Heydte, would occupy the Eupen-Verviers intersection, but due to heavy anti-aircraft fire and inexperience of the pilots, only two hundred men ended up in the designated dropping area. The others landed scattered - some even near Bonn - and were quickly put out of action. Von der Heydte managed to gather another three hundred men, but considered that too little to occupy the intersection. He limited himself to intercepting Allied couriers. When the 12. SS-Panzer-Division did not show up, Von der Heydte decided to break out to the east. However, most of the troops, including himself, did not reach the German lines and were forced to surrender.

Massacre at Malmedy

The Malmedy Massacre was a war crime in World War II in which 84 American prisoners of war were killed by the Germans. The massacre took place on December 17, 1944 by Kampfgruppe Peiper, a German combat unit during the Battle of the Bulge.

During the Battle of the Bulge, the 6th SS Panzer Army commanded by General Sepp Dietrich was ordered to break through the Allied lines of defense between Monschau and Losheimergraben. Their goal was to conquer Antwerp. Kampfgruppe Peiper was part of the 6th SS Panzer Army. After the Kampfgruppe broke through the American lines, it became Peiper's task to capture the Maas bridge around Huy. The best roads were reserved for the 1. SS-Panzer-Division Leibstandarte-SS Adolf Hitler. Peiper had to use the secondary roads, which turned out to be useless for the heavy vehicles of his Kampfgruppe. In order for his mission to succeed, Peiper had to quickly conquer the bridges. To do this, he and his Kampfgruppe had to advance through an area that had already been conquered by the Americans. Another problem was that the Kampfgruppe ran out of fuel. Finally, Hitler had given orders to terrify the enemy with a swift and merciless attack. Sepp Dietrich confirmed this during the trials.

Right from the start, the German operations at the front did not go smoothly because of the great resistance of the American soldiers. Peiper hoped to make use of an opening in the defense line on December 16, the first day of the offensive. In reality, however, he was held up by major traffic jams behind the front while the German infantry, who had to punch a hole in the American lines, awaited his arrival. Only on December 17 did the Kampfgruppe manage to break through towards Honsfeld. This is where the first massacre took place. Soldiers of Peipers Kampfgruppe murdered dozens of American prisoners of war.

After capturing Honsfeld, Peiper deviated a few kilometers from his assigned route in hopes of capturing a fuel depot in Büllingen. Later a massacre of prisoners of war took place there. At this point, Peiper was behind the enemy. Had he gone from Büllingen to Elsenborn, he could have secured two American units. However, Peiper decided to return to his old route and conquer Ligneuville first. This decision proved difficult due to the difficult terrain and the poor quality of the roads. In the end it turned out to be impossible to travel directly to Ligneuville and Peiper was forced to deviate from his route again. He and his Kampfgruppe therefore moved towards the intersection of Baugnez, which was located between Malmedy, Ligneuville and Waimes.

The German Kampfgruppe reached the intersection between 12 noon and 1 pm. Meanwhile, an American convoy of 30 vehicles, mostly belonging to the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion (FAOB), was on its way to Ligneuville. The goal was to rejoin the US 7th Armored Division at St. Vith. Peiper's group saw the convoy and opened fire. By taking out the first and last vehicle in the column, the Germans brought the entire convoy to a stop. The soldiers of the convoy had only rifles and small firearms. They soon had to surrender.

While the Kampfgruppe headed by Peiper moved on towards Ligneuville, the captured Americans were taken to a field where other prisoners were also located. According to witnesses, 120 prisoners were present on the field. For reasons still unknown, the Germans unexpectedly opened fire. It is now generally believed that some prisoners from the back rows had tried to escape to the forest where the German guards started firing and a general panic broke out. Some claim that a number of prisoners had managed to take back their weapons and fired upon the Germans. Of the 88 bodies found a month later, more than 20 had gunshot wounds to the head. This possibly suggested an execution of the seriously wounded prisoners of war.

As soon as the Germans started firing, some of the prisoners tried to flee. Most were shot during their attempt to escape, but a few made it to a café. The Germans set fire to the building, and shot and killed the prisoners who tried to leave the burning building. Some prisoners tried to escape the massacre by dropping and pretending to be dead. The German troops, however, acted on the safe side and checked all the bodies. If any living prisoners were found among them, they were still killed. This immediately explains the relatively high number of gunshot wounds to the head.

Despite everything, a few prisoners survived. They managed to reach the American troops at Malmedy. In total, 43 survivors reached the Allied forces. Immediately after their arrival at the front, the survivors were interrogated. They all made the same statement about the massacre that had taken place.

The first survivors of the massacre were picked up by a patrol from the 291st Combat Engineer Battalion at around 2:30 am. The First Army Inspector General heard about the massacre three to four hours later. Later that day, stories of the German atrocity reached American troops. As a result, an American unit decided not to take any more prisoners, but to execute every German on the spot. As the Baugnez crossing was a no man's land until the Allies successfully counterattacked, the bodies were not discovered until around January 14, 1945. The bodies were photographed and taken for autopsy and identification. Ultimately, 72 bodies were found in the field, and another 12 further on. Autopsy showed that at least 20 of the victims had bullet wounds to their heads from a close-range shot. Some other bodies had only a single gunshot wound to the temple. In addition, most of the bodies were grouped together in a small area, suggesting that the victims had been gathered together for surveillance shortly before the escape attempt that led to the shooting.

This massacre was the subject of a lawsuit during the Dachau Trials in 1946. All convicted prisoners were released during the 1950s. The last to be released was Peiper, in December 1956. He died in 1976 when former members of the resistance burned down his house in France

"NUTS!"

On December 22, 1944, von Lüttwitz dispatched a party, consisting of a major, a lieutenant, and two enlisted men under a flag of truce to deliver an ultimatum. Entering the American lines southeast of Bastogne (occupied by Company F, 2nd Battalion, 327th Glider Infantry), the German party delivered the following to General McAuliffe. According to those present when McAuliffe received the German message, he read it, crumpled it into a ball, threw it in a wastepaper basket, and muttered, "Aw, nuts". The officers in McAuliffe's command post were trying to find suitable language for an official reply when Lt. Col. Harry Kinnard suggested that McAuliffe's first response summed up the situation pretty well, and the others agreed. The official reply was typed and delivered by Colonel Joseph Harper, commanding the 327th Glider Infantry, to the German delegation. It was as follows:

To the German Commander.

NUTS!

The American Commander.

Allied counter-offensive

On January 3, the coordinated Allied counterattack began in the Ardennes. Montgomery was to move south from the north over a 40-kilometer front with the US 1st Army and British XXXth Corps, where the US 3rd Army moved north from the south. Initially, Montgomery made very slow progress, partly because the weather was bad with a snow cover of one meter and fierce cold. As a result, the roads were slippery and visibility was generally no more than two hundred meters. Heavy snowfall even halted the attacks for a few days. And even after that, meter by meter had to be conquered from an opponent who had dug into the inhospitable landscape with tanks and anti-tank guns. In the south, where Omar Bradley was in command, the battle was no less arduous. Hitler still wanted to conquer Bastogne. The Germans concentrated ten divisions on this. Scarce resources were thus wasted on a prestige issue.

The fierce attacks made it even more difficult for the Americans. The American 6th Armored Division was pushed back head-on by the 12. SS Panzer-Division Hitlerjugend; only an artillery barrage could prevent a collapse. An American soldier inspects a wreckage of a Panzerkampfwagen IV, an older model that was still widely used in 1944 From January 5, the German pressure decreased. Although Montgomery and Bradley made little progress, the situation was now very dire for the Germans. On 7 January there were seven German panzer divisions west of the Liège-Houffalize-Bastogne line and there was only one way back: through Houffalize. However, that town was bombed on the night of January 6 to hinder the German movements. It was then under continuous allied barrage. Now it also became clear to Hitler that encirclement was imminent. He ordered a limited retreat behind this line on January 8. The next day the Allies noticed that the German armored units in particular were starting to break away from the front. The SS units were saved as a matter of priority. Slowly in the days that followed, the Allies advanced. On January 10, La Roche-en-Ardenne fell to the Allies. On January 11, Saint-Hubert was captured and on January 16 the soldiers of the US 1st Army coming from the north and the US 3rd Army coming from the south reached out amid the ruins of Houffalize. At that point all the larger German units had already escaped to the east.

A day later, the US 1st Army came back under Bradley's command; the US 9th Army remained under Montgomery. It was a solution that satisfied neither commanding officer. While Eisenhower's earlier decision to place the 1st and 9th Armies under Montgomery's command had been militarily correct, Bradley could not have tolerated it. Montgomery even attempted to become the overall field forces commander of all troops on the Western Front again, as he had been during the Battle of Normandy. It was only when his own staff made it clear to him that an exasperated Eisenhower was about to demand that the British government be called back to the homeland, Montgomery backed down. In a press conference about the battle, however, he made it appear in smug terms as if he had led it and brought it to a successful conclusion on his own. The German propaganda service fired even more between the two allies by broadcasting fake British radio programs extolling Montgomery and portraying Bradley as an incompetent dork who had been spared total defeat only with British help.

With the capture of Houffalize, the German salient had been cleared and the Battle of the Bulge strategically ended. Over the next twelve days, the Americans pushed the Germans back to the West Wall. Partly due to actions by the Allied Air Force, the Germans lost large amounts of equipment on the way back. For the rest, the battle was slowly coming to an end. During the last two weeks, the Allied staff quarters worked mainly on the plans for the attack on the Roer and Rhine.

On January 15, Hitler had left his headquarters in Ziegenberg and went to Berlin. The 6th Panzer Army was recalled from the Ardennes on January 20 to deploy it on the Eastern Front, for on January 12 the Soviet troops had set in motion for their massive offensive over the Vistula. At the end of January, the front line of December 15 was reached again. On the eastern front, however, the Germans were pushed further and further back. East Prussia was cut off from the Reich and the Red Army reached the Oder. The Soviets also managed to conquer the Upper Silesian industrial area.

In the late autumn of 1944, the Allies had become so accustomed to thinking that the Wehrmacht was on the verge of collapse that the Battle of the Bulge came as a complete surprise. The offensive led to panic reactions in several places, albeit not at the highest level. Eisenhower in particular proved his great qualities as a coordinator, who managed to control the tensions in the Allied camp (the one with the French over Strasbourg and that between Bradley and Montgomery over command) well.

Casualties

Although the British also fought in the Battle of the Bulge, their role was limited. Only 2% of the Allied losses were accounted for. In addition to the great loss of human life, a large number of tanks were also lost. In the Ardennes 733 tanks were put out of action by the Germans. In addition, 529 aircraft were lost. For the Germans, the human and material losses during this daring attack were also great. In the Ardennes, 324 German tanks, 320 aircraft and 6.000 vehicles were irreparably damaged by the Allies. Hitler managed to postpone the frontal attack on the West Wall for six weeks with his offensive. The big difference between the Allied and the German losses was that the Allied could be replaced and the German could not. The Germans could no longer close breaches in the front; the allies could now advance from the west as well as from the east to the next target. The Battle of the Bulge robbed the eastern front of an urgently needed armor reserve. In the east, the Germans could not stop the breakthrough Soviet Union troops and the Soviets were soon close to Berlin. The German troops, spread over two fronts, could never turn the tide against the advancing armies. In addition to the fronts in the East and the West, there was the Italian front in the South, where more than 439.000 German troops with some 160.000 Italians were stationed.