Duration of this batte: 19 February - 26 March 1945

Battle of Iwo Jima

Commanders of the Battle of Iwo Jima

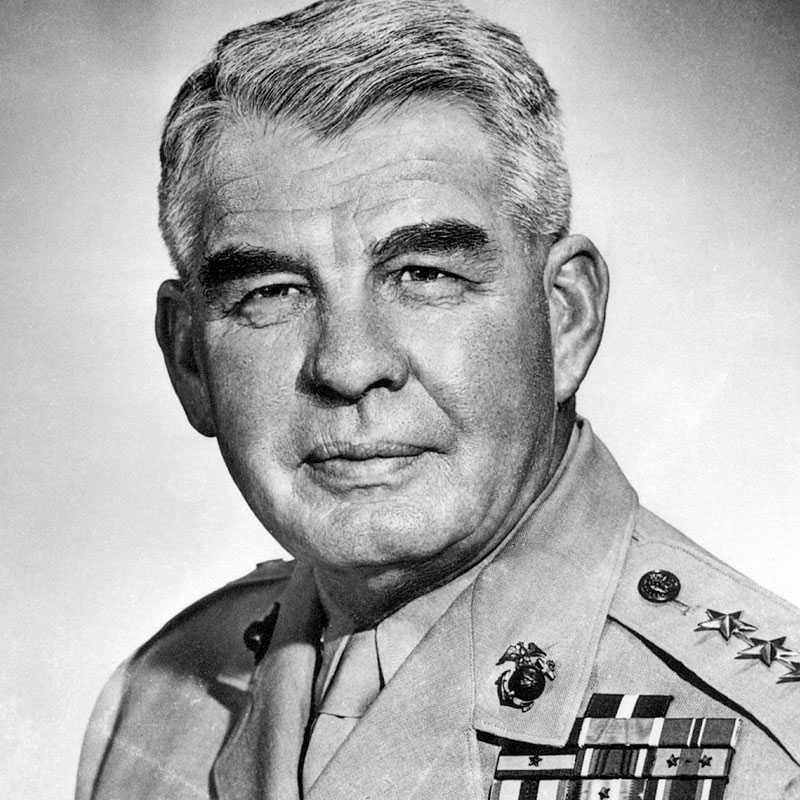

Harry Schmidt

Tadamichi Kuribayashi

The Battle of Iwo Jima (19 February- 26 March 1945), or Operation Detachment, was a major battle in which the United States Armed Forces fought for and captured the island of Iwo Jima from the Japanese Empire. The American invasion had the goal of capturing the entire island, including its three airfields (including South Field and Central Field), to provide a staging area for attacks on the Japanese main islands. This five-week battle comprised some of the fiercest and bloodiest fighting of the War in the Pacific of World War II.

After the heavy losses incurred in the battle, the strategic value of the island became controversial. It was useless to the Army as a staging base and useless to the Navy as a fleet base.

The Imperial Japanese Army positions on the island were heavily fortified, with a dense network of bunkers, hidden artillery positions, and 18 km (11 mi) of underground tunnels. The Americans on the ground were supported by extensive naval artillery and complete air supremacy over Iwo Jima from the beginning of the battle by U.S. Navy and Marine Corps aviators. This invasion was the first American attack on Japanese home territory, and the Japanese soldiers and marines defended their positions tenaciously with no thought of surrender.

Iwo Jima was the only battle by the U.S. Marine Corps in which the overall American casualties (killed and wounded) exceeded those of the Japanese, although Japanese combat deaths were thrice those of the Americans throughout the battle. Of the 22.000 Japanese soldiers on Iwo Jima at the beginning of the battle, only 216 were taken prisoner, some of whom were captured because they had been knocked unconscious or otherwise disabled. The majority of the remainder were killed in action, although it has been estimated that as many as 3000 continued to resist within the various cave systems for many days afterwards, eventually succumbing to their injuries or surrendering weeks later.

Despite the bloody fighting and severe casualties on both sides, the Japanese defeat was assured from the start. American overwhelming superiority in arms and numbers as well as complete control of air power — coupled with the impossibility of Japanese retreat or reinforcement- permitted no plausible circumstance in which the Americans could have lost the battle.

The battle was immortalized by Joe Rosenthal's photograph of the raising of the U.S. flag on top of the 166 m (545 ft) Mount Suribachi by five U.S. Marines and one U.S. Navy battlefield Hospital Corpsman. The photograph records the second flag-raising on the mountain, both of which took place on the fifth day of the 35-day battle. Rosenthal's photograph promptly became an indelible icon of that battle, of that war in the Pacific, and of the Marine Corps itself and has been widely reproduced.

After the American capture of the Marshall Islands, and the devastating air attacks against the Japanese fortress island of Truk Atoll in the Carolines in January 1944, the Japanese military leaders reevaluated their situation. All indications pointed to an American drive toward the Mariana Islands and the Carolines. To counter such an offensive, the Imperial Japanese Army and the Imperial Japanese Navy (I.J.N.) established an inner line of defenses extending generally northward from the Carolines to the Marianas, and thence to Japan via the Volcano Islands, and westward from the Marianas via the Carolines and the Palau Islands to the Philippines.

In March 1944, the Japanese 31st Army, commanded by General Hideyoshi Obata, was activated to garrison this inner line. (Note that a Japanese "army" was about the size of an American, British Army, or Canadian Army corps. The Japanese Army had many armies[quantify], but the U.S. Army only had ten at its peak, with the 4th Army, the 6th Army, the 8th Army, and the 10th Army being in the Pacific Theater. Also, the 10th Army only fought on Okinawa in the spring of 1945.)

The commander of the Japanese garrison on Chichi Jima was placed nominally in command of Army and Navy units in the Volcano Islands. After the American conquest of the Marianas, daily bomber raids from the Marianas hit the mainland as part of Operation Scavenger. Iwo Jima served as an early warning station that radioed reports of incoming bombers back to mainland Japan. This allowed Japanese air defenses to prepare for the arrival of American bombers.

After the U.S. seized bases in the Marshalls in the battles of Kwajalein and Eniwetok in February 1944, Japanese Army and Navy reinforcements were sent to Iwo Jima: 500 men from the naval base at Yokosuka and 500 from Chichi Jima reached Iwo Jima during March and April 1944. At the same time, with reinforcements arriving from Chichi Jima and the home islands, the Army garrison on Iwo Jima reached a strength of more than 5,000 men. The loss of the Marianas during the summer of 1944 greatly increased the importance of the Volcano Islands for the Japanese, who were aware that the loss of these islands would facilitate American air raids against the Home Islands, disrupting war manufacturing and severely damaging civilian morale. Final Japanese plans for the defense of the Volcano Islands were overshadowed by the fact that the Imperial Japanese Navy had already lost almost all of its power, and it could not prevent American landings. Moreover, aircraft losses throughout 1944 had been so heavy that, even if war production were not affected by American air attacks, combined Japanese air strength was not expected to increase to 3,000 warplanes until March or April 1945. Even then, these planes could not be used from bases in the Home Islands against Iwo Jima because their range was not more than 900 km (560 mi). Besides this, all available warplanes had to be hoarded to defend Taiwan and the Japanese Home Islands from any attack. Adding to their woes, there was a serious shortage of properly trained and experienced pilots and other aircrew to man the warplanes Japan had—because such large numbers of pilots and crewmen had perished fighting over the Solomon Islands and during the Battle of the Philippine Sea in mid-1944.

At the end of the Battle of Leyte in the Philippines, the Allies were left with a two-month lull in their offensive operations before the planned invasion of Okinawa. Iwo Jima was strategically important: it provided an air base for Japanese fighter planes to intercept long-range B-29 Superfortress bombers, and it provided a haven for Japanese naval units in dire need of any support available. In addition, it was used by the Japanese to stage air attacks on the Mariana Islands from November 1944 through January 1945. The capture of Iwo Jima would eliminate these problems and provide a staging area for Operation Downfall - the eventual invasion of the Japanese Home Islands. The distance of B-29 raids could (hypothetically) be cut in half, and a base would be available for P-51 Mustang fighters to escort and protect the bombers.

Intelligence sources were confident that Iwo Jima would fall in one week. In light of the optimistic intelligence reports, the decision was made to invade Iwo Jima: this amphibious landing was given the code name Operation Detachment. They were unaware that the Japanese were preparing a complex and deep defense, radically departing from their usual strategy. So successful was the Japanese preparation that it was discovered after the battle that the hundreds of tons of Allied bombs and thousands of rounds of heavy naval gunfire left the Japanese defenders almost unscathed and ready to inflict losses on the U.S. Marines unprecedented up to that point in the Pacific War.

United States Marine Corps (USMC)

Imperial Japanse army

Battle specifications

Date of the battle

Duration of the battle

Reason for the battle

Location

Battle result

Allied casualties

-

Killed: 6.102

-

Wounded: 19.709

-

Planes lost: 153

-

Vehicles lost: 137

Axis casualties

-

Killed: 18.375

-

Wounded: not known

-

Planes lost: not known

-

Vehicles lost: not known

Planning and preparation

By June 1944, Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi was assigned to command the defense of Iwo Jima. Kuribayashi knew that Japan could not win the battle, but he hoped to inflict massive casualties on the American forces, so that the United States and its Australian and British allies would reconsider carrying out the invasion of Japan Home Islands.

While drawing inspiration from the defense in the Battle of Peleliu, Kuribayashi designed a defense that broke with Japanese military doctrine. Rather than establishing his defenses on the beach to face the landings directly, he created strong, mutually supporting defensive defenses in depth using static and heavy weapons such as heavy machine guns and artillery. Takeichi Nishi's armored tanks were to be used as camouflaged artillery positions. Because the tunnel linking the mountain to the main forces was never completed, Kuribayashi organized the southern area of the island in and around Mount Suribachi as a semi-independent sector, with his main defensive zone built up in the north. The expected American naval and air bombardment further prompted the creation of an extensive system of tunnels that connected the prepared positions, so that a pillbox that had been cleared could be reoccupied. This network of bunkers and pillboxes favored the defense. Hundreds of hidden artillery and mortar positions along with land mines were placed all over the island. Among the Japanese weapons were 320 mm spigot mortars and a variety of explosive rockets.

Numerous Japanese snipers and camouflaged machine gun positions were also set up. Kuribayashi specially engineered the defenses so that every part of Iwo Jima was subject to Japanese defensive fire. He also received a handful of kamikaze pilots to use against the enemy fleet. Three hundred eighteen American sailors were killed by Kamikaze attacks during the battle. However, against his wishes, Kuribayashi's superiors on Honshu ordered him to erect some beach defenses. These were the only parts of the defenses that were destroyed during the pre-landing bombardment.

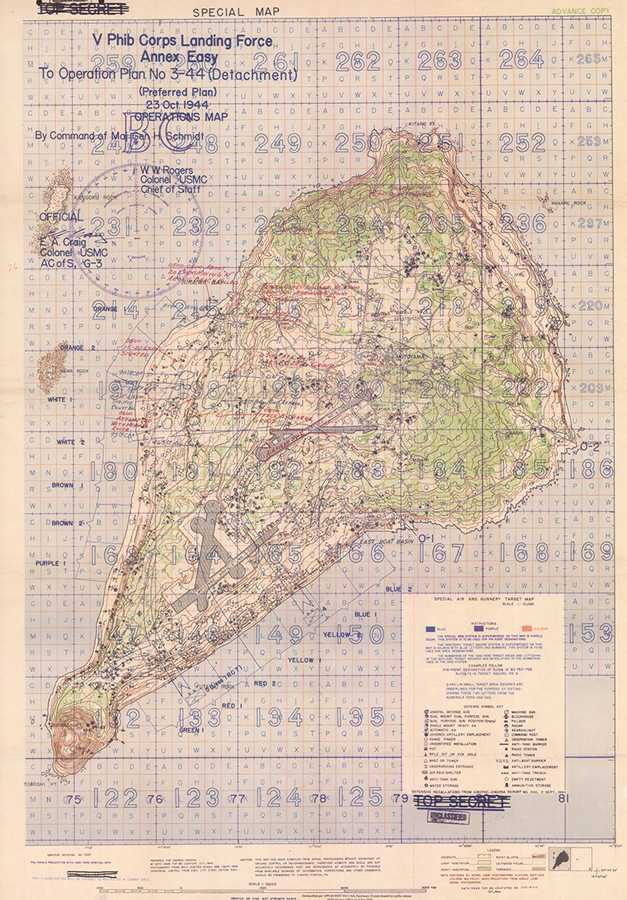

Amphibious landing

Starting on 15 June 1944, the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army Air Forces began naval bombardments and air raids against Iwo Jima that would become the longest and most intense conflict in the Pacific theater. These would contain a combination of naval artillery shellings and aerial bombings that went on for nine months. Major General Harry Schmidt of the Marine Corps requested a 10-day heavy shelling of Iwo Jima before the amphibious assault, but was given only three days, and these were impaired by the weather conditions. Each heavy warship was given an area on which to fire that, combined with all the ships, covered the entire island. Each warship fired for approximately six hours before stopping for a certain amount of time.

The American bombings and bombardments continued through 19 February 1945, the day of the amphibious landing, known operationally as D-Day. The limited bombardment had questionable success on the enemy due to the Japanese being heavily dug-in and fortified. However, many bunkers and caves were destroyed during the bombing giving it some limited success. The Japanese had been preparing for this battle since March 1944, which gave them a significant head start. By the time of the landing, about 450 American ships were located off Iwo Jima. The entire battle involved about 60.000 U.S. Marines and several thousand U.S. Navy Seabees.

At 08:59, one minute ahead of schedule, the first of an eventual 30.000 Marines of the 3rd Marine Division, the 4th Marine Division, and the new 5th Marine Division, making up the V Amphibious Corps, landed on the beach. The initial wave was not hit by Japanese fire for some time. General Kuribayashi's plan was to wait until the beach was full of the Marines and their equipment.

Many of the Marines who landed on the beach in the first wave speculated that perhaps the naval and air bombardment of the island had killed all of the Japanese troops that were expected to be defending the island. In the deathly silence, they became somewhat unnerved as Marine patrols began to advance inland in search of the Japanese positions. Only after the front wave of Marines reached a line of Japanese bunkers defended by machine gunners did they take hostile fire. Many concealed Japanese bunkers and firing positions opened up, and the first wave of Marines took devastating losses from the machine guns. Aside from the Japanese defenses situated on the beaches, the Marines faced heavy fire from Mount Suribachi at the south of the island. It was extremely difficult for the Marines to advance because of the inhospitable terrain, which consisted of volcanic ash. This ash allowed for neither a secure footing nor the construction of foxholes to protect the Marines from hostile fire. However, the ash did help to absorb some of the fragments from Japanese artillery.

The Japanese heavy artillery in Suribachi opened their reinforced steel doors to fire, and then closed them immediately to prevent counterfire from the Marines and naval gunners. This made it difficult for American units to destroy a piece of Japanese artillery. To make matters worse for the American troops, the bunkers were connected to the elaborate tunnel system so that bunkers that were cleared with flamethrowers and grenades were reoccupied shortly afterwards by Japanese troops moving through the tunnels. This Japanese tactic caused many casualties among the Marines, as they walked past the reoccupied bunkers without expecting to suddenly take fresh fire from them. The Marines advanced slowly while taking heavy machine gun and artillery fire. With the arrival of armored tanks, and by the use of heavy naval artillery and aerial bombing on Mount Suribachi, the Marines were able to advance past the beaches. Seven hundred sixty Marines made a near-suicidal charge across to the other side of Iwo Jima on that first day. They took heavy casualties, but they made a considerable advance. By the evening, the mountain had been cut off from the rest of the island, and 30.000 Marines had landed. About 40.000 more would follow.

In the days after the landings, the Marines expected the usual Japanese banzai charge during the night. This had been the standard Japanese final defense strategy in previous battles against enemy ground forces in the Pacific, such as during the Battle of Saipan. In those attacks, for which the Marines were prepared, the majority of the Japanese attackers had been killed and the Japanese strength greatly reduced. However, General Kuribayashi had strictly forbidden these "human wave" attacks by the Japanese infantrymen because he considered them to be futile.

The fighting on the beachhead at Iwo Jima was very fierce. The advance of the Marines was stalled by numerous defensive positions augmented by artillery pieces. There, the Marines were ambushed by Japanese troops who occasionally sprang out of tunnels. At night, the Japanese left their defenses under cover of darkness to attack American foxholes, but U.S. Navy ships fired star shells to deny them cover of darkness. Many Japanese soldiers who knew English would deliberately call for a Navy corpsman, and then shoot them as they approached. The Marines learned that firearms were relatively ineffective against the Japanese defenders and effectively used flamethrowers and grenades to flush out Japanese troops in the tunnels. One of the technological innovations of the battle, the eight Sherman M4A3R3 medium tanks equipped with a flamethrower ("Ronson" or "Zippo" tanks), proved very effective at clearing Japanese positions. The Shermans were difficult to disable, such that defenders were often compelled to assault them in the open, where the Japanese troops would fall victim to the superior numbers of Marines. Close air support (CAS) was initially provided by fighters from escort carriers off the coast. This shifted over to the 15th Fighter Group, flying P-51 Mustangs, after they arrived on the island on 6 March. Similarly, illumination rounds (flares) which were used to light up the battlefield at night were initially provided by ships, shifting over later to landing force artillery. Navajo code talkers were part of the American ground communications, along with walkie-talkies and SCR-610 backpack radio sets.

After running out of water, food and most supplies, the Japanese troops became desperate toward the end of the battle. Kuribayashi, who had argued against banzai attacks at the start of the battle, realized that Japanese defeat was imminent. Marines began to face increasing numbers of nighttime attacks; these were only repelled by a combination of machine gun defensive positions and artillery support. At times, the Marines engaged in hand-to-hand fighting to repel the Japanese attacks. With the landing area secure, more troops and heavy equipment came ashore and the invasion proceeded north to capture the airfields and the remainder of the island. Most Japanese soldiers fought to the death.

U.S. flag over Mount Suribachi

"Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima" is a historic photograph taken on 23 February 1945 by Joe Rosenthal. It depicts five Marines and a U.S. Navy corpsman raising the flag of the United States atop Mount Suribachi. The photograph was extremely popular, being reprinted in thousands of publications. Later, it became the only photograph to win the Pulitzer Prize for Photography in the same year as its publication, and ultimately came to be regarded as one of the most significant and recognizable images of the war, and possibly the most reproduced photograph of all time.[11] Of the six men depicted in the picture, three (Franklin Sousley, Harlon Block, and Michael Strank) did not survive the battle; the three survivors (John Bradley, Rene Gagnon, and Ira Hayes) became celebrities upon the publication of the photo. For a while, it was believed that the man now known to be Block was actually Hank Hansen, but Hayes set the record straight. The picture was later used by Felix de Weldon to sculpt the Marine Corps War Memorial, located adjacent to Arlington National Cemetery.

By the morning of 23 February, Mount Suribachi was effectively cut off above ground from the rest of the island. The Marines knew that the Japanese defenders had an extensive network of below-ground defenses, and knew that in spite of its isolation above ground, the volcano was still connected to Japanese defenders via the tunnel network. They expected a fierce fight for the summit. Two four-man patrols were sent up the volcano to reconnoiter routes on the mountain's north face. Popular legend (embroidered by the press in the aftermath of the release of the famous photo) has it that the Marines fought all the way up to the summit. Although American riflemen expected an ambush, they encountered only small groups of Japanese defenders on Suribachi. The majority of the Japanese troops stayed in the tunnel network, only occasionally attacking in small groups, and were generally all killed. The patrols made it to the summit and scrambled down again, reporting the lack of enemy contact to Colonel Chandler Johnson. Johnson then called for a platoon of Marines to climb Suribachi; with them, he sent a small American flag to fly if they reached the summit. The Marines again anticipated an ambush, but they reached the top of Mount Suribachi without incident. Using a length of pipe they found among the wreckage atop the mountain, the Marines hoisted the U.S. flag over Mount Suribachi: the first foreign flag to fly on Japanese soil. A photograph of this "first flag raising" was taken by photographer Louis R. Lowery.

As the flag went up, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal had just landed on the beach at the foot of Mount Suribachi and decided that he wanted the flag as a souvenir. Popular legend has it that Colonel Johnson wanted the flag for himself, but, in fact, he believed that the flag belonged to the 2nd Battalion 28th Marines, who had captured that section of the island. Johnson sent Sergeant Mike Strank to take a second (larger) flag up the volcano to replace the first. It was as the replacement flag went up that Rosenthal took the famous photograph "Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima".

Northern Iwo Jima

Despite Japan's loss of Mount Suribachi on the south end of the island, the Japanese still held strong positions on the north end. The rocky terrain vastly favored defense, even more so than Mount Suribachi, which was much easier to hit with naval artillery fire. Coupled with this, the fortifications constructed by Kuribayashi were more impressive than at the southern end of the island. Remaining under the command of Kuribayashi was the equivalent of eight infantry battalions, a tank regiment, and two artillery and three heavy mortar battalions. Also he had about 5.000 gunners and naval infantry. The most arduous task left to the Marines was the overtaking of the Motoyama Plateau with its distinctive Hill 382 and Turkey knob and the area in between referred to as the Amphitheater. This formed the basis of what came to be known as the "meatgrinder". While this was being achieved on the right flank, the left was clearing out Hill 362 with just as much difficulty. The overall objective at this point was to take control of Airfield No. 2 in the center of the island. However, every "penetration seemed to become a disaster" as "units were raked from the flanks, chewed up sometimes wiped out. Tanks were destroyed by interlocking fire or were hoisted into the air on the spouting fireballs of buried mines". As a result, the fighting bogged down, with American casualties piling up. Even capturing these points was not a solution to the problem since a previously secured position could be attacked from the rear by the use of the tunnels and hidden pillboxes. As such, it was said that "they could take these heights at will, and then regret it".

The Marines nevertheless found ways to prevail under the circumstances. It was observed that during bombardments, the Japanese would hide their guns and themselves in the caves only to reappear when the troops would advance and lay devastating fire on them. The Japanese had over time learned basic American strategy which was to lay heavy bombardment before an infantry attack. Consequently, General Erskine ordered the 9th Marine Regiment to attack under the cover of darkness with no preliminary barrage. This came to be a resounding success with many soldiers taken out while still sleeping. This was a key moment in the capture of Hill 362. It held such importance that the Japanese organized a counterattack the following night. Although Kuribayashi had forbidden the suicide charges familiar with other battles in the Pacific, the commander of the area decided on a banzai charge with the optimistic goal of recapturing Mount Suribachi. On the evening of 8 March, Captain Samaji Inouye and his 1.000 men charged the American lines inflicting 347 casualties (90 deaths). The Marines counted 784 dead Japanese soldiers the next day. There was also a kamikaze air attack (the only one of the battle) on the ships anchored at sea on 21 February, which resulted in the sinking of the escort carrier USS Bismarck Sea, severe damage to USS Saratoga and slight damage to the escort carrier USS Lunga Point, an LST and a transport.

Although the island was declared secure at 18:00 on 16 March 25 days after the landings, the 5th Marine Division still faced Kuribayashi's stronghold in a gorge 640 m (700 yd) long at the northwestern end of the island. On 21 March, the Marines destroyed the command post in the gorge with four tons of explosives and on 24 March, Marines sealed the remaining caves at the northern tip of the island. However, on the night of 25 March, a 300-man Japanese force launched a final counterattack in the vicinity of Airfield No. 2. Army pilots, Seabees and Marines of the 5th Pioneer Battalion and 28th Marines fought the Japanese force for up to 90 minutes but suffered heavy casualties (53 killed, 120 wounded). Two Marines from the 36th Depot Company, an all-African-American unit, received the Bronze Star. 1st Lieutenant Harry Martin of the 5th Pioneer Battalion was the last Marine to be awarded the Medal of Honor during the battle. Although still a matter of speculation because of conflicting accounts from surviving Japanese veterans, it has been said that Kuribayashi led this final assault, which unlike the loud banzai charge of previous battles, was characterised as a silent attack. If ever proven true, Kuribayashi would have been the highest ranking Japanese officer to have personally led an attack during World War II. Additionally, this would also be Kuribayashi's final act, a departure from the normal practice of the commanding Japanese officers committing seppuku behind the lines while the rest perished in the banzai charge, as happened during the battles of Saipan and Okinawa. The island was officially declared secure at 09:00 on 26 March.

Aftermath

Of the 22,060 Japanese soldiers entrenched on the island, 18.844 died either from fighting or by ritual suicide. Only 216 were captured during the course of battle. After Iwo Jima, it was estimated there were no more than 300 Japanese left alive in the island's warren of caves and tunnels. In fact, there were close to 3.000. The Japanese bushido code of honor, coupled with effective propaganda which portrayed American G.I.s as ruthless animals, prevented surrender for many Japanese soldiers. Those who could not bring themselves to commit suicide hid in the caves during the day and came out at night to prowl for provisions. Some did eventually surrender and were surprised that the Americans often received them with compassion, offering water, cigarettes, or coffee. The last of these holdouts on the island, two of Lieutenant Toshihiko Ohno's men, Yamakage Kufuku and Matsudo Linsoki, lasted four years without being caught and finally surrendered on 6 January 1949.

According to the official Navy Department Library website, "The 36-day (Iwo Jima) assault resulted in more than 26.000 American casualties, including 6.800 dead." By comparison, the much larger scale 82-day Battle for Okinawa lasting from early April until mid-June 1945 and U.S. (5 Army and 2 Marine Corps Divisions) resulted in casualties of over 62.000 of whom over 12.000 were killed or missing. Iwo Jima was also the only U.S. Marine battle where the American casualties exceeded the Japanese, although Japanese combat deaths numbered three times as many American deaths. Two US Marines were captured as POWs during the battle; neither of them would survive their captivity. USS Bismarck Sea was also lost, the last U.S. aircraft carrier sunk in World War II. Because all civilians had been evacuated, there were no civilian casualties at Iwo Jima, unlike at Saipan and Okinawa.