23 August 1942 - 2 February 1943

Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 1942 - 2 February 1943) is one of the turning points of World War 2 in which German troops of the 6th Army and its allies fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (now Volgograd) in the southwestern Soviet Union. Marked by constant close quarters combat and disregard for military and civilian casualties, it is among the bloodiest battles in the history of warfare. The 6th Army was eventually completely destroyed by the Red Army, which appeared to be nearly defeated just a few months earlier. The Battle of Stalingrad (present-day Volgograd) became the symbol of the resurrection of the Red Army and dealt a heavy blow to German morale; it dawned on broad sections of the German population that the war might end badly for Germany; the Nazi regime from now on abandoned 'cannons instead of butter' propaganda and, after the battle, called on the people to all-out war.

In 1941, Germany had attempted to inflict rapid and total defeat on the Soviet Union through Operation Barbarossa. That had failed because they got stuck in the autumn mud in October. In winter, a counter-offensive threw the Germans a few hundred kilometers back from Moscow. In December Hitler declared war on the United States of America. In the spring of 1942 the German army was still very much weakened. Most divisions were under severe strength. There were shortages of equipment, ammunition and fuel. This situation could not be remedied quickly because Hitler, who had always feared a confrontation with the US, had already increased the production of submarines and airplanes in 1940 at the expense of rapidly building up army equipment. Thus, the arms industry had to be converted to sustain a protracted war in the East. Another structural problem was that, even after the loss of the western regions, the Soviet Union had twice the reserve of manpower than Germany to fight the Battle of Stalingrad.

Soviet Red Army

German Wehrmacht

Battle specifications

Date of the battle

Duration of the battle

Reason for the battle

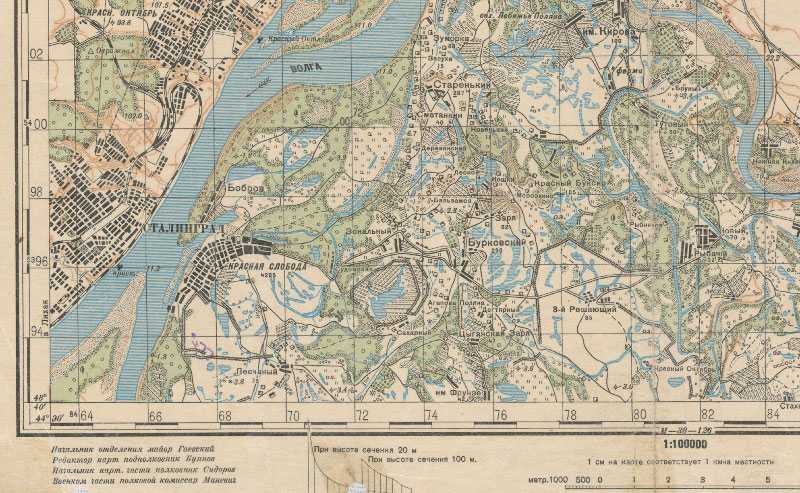

Location

Battle result

Allied casualties

-

Killed: 1.129.619

-

Planes lost: 2.769

-

Vehicles lost: 4.341

Axis casualties

-

Killed: 647.300 - 968.374

-

Planes lost: 1.000

Commanders of the Battle of Stalingrad

Joseph Stalin

Friedrich Paulus

The German offensive to capture Stalingrad during the Battle of Stalingrad began in late summer 1942 using the 6th Army and elements of the 4th Panzer Army. The attack was supported by intensive Luftwaffe bombing that reduced much of the city to rubble. The fighting degenerated into building-to-building fighting, and both sides poured reinforcements into the city. By mid-November 1942, the Germans had pushed the Soviet defenders back at great cost into narrow zones generally along the west bank of the Volga River.

On 19 November 1942, the Red Army launched Operation Uranus, a two-pronged attack targeting the weaker Romanian and Hungarian forces protecting the German 6th Army's flanks. The Axis forces on the flanks were overrun and the 6th Army was cut off and surrounded in the Stalingrad area. Adolf Hitler ordered that the army stay in Stalingrad and make no attempt to break out; instead, attempts were made to supply the army by air and to break the encirclement from outside. Heavy fighting continued for another two months. By the beginning of February 1943, the Axis forces in Stalingrad had exhausted their ammunition and food. The remaining elements of the 6th Army surrendered. The battle lasted five months, one week, and three days.

The heavy losses inflicted on the Wehrmacht at the Battle of Stalingrad make it arguably the most strategically decisive battle of the whole war. It was a turning point in the European theatre of WW2 the German forces never regained the initiative in the East and withdrew a vast military force from the West to reinforce their losses.

The German public was not officially told of the impending disaster at The Battle of Stalingrad until the end of January 1943, though positive media reports had stopped in the weeks before the announcement. Stalingrad marked the first time that the Nazi government publicly acknowledged a failure in its war effort. On 31 January, regular programmes on German state radio were replaced by a broadcast of the sombre Adagio movement from Anton Bruckner's Seventh Symphony, followed by the announcement of the defeat at Stalingrad. On 18 February, Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels gave the famous Sportpalast speech in Berlin, encouraging the Germans to accept a total war that would claim all resources and efforts from the entire population.

Based on Soviet records, over 10.000 German soldiers continued to resist in isolated groups within the city for the next month. Some have presumed that they were motivated by a belief that fighting on was better than a slow death in Soviet captivity. Brown University historian Omer Bartov claims they were motivated by National Socialism. He studied 11,237 letters sent by soldiers inside of Stalingrad between 20 December 1942 and 16 January 1943 to their families in Germany. Almost every letter expressed belief in Germany's ultimate victory and their willingness to fight and die at Stalingrad to achieve that victory. Bartov reported that a great many of the soldiers were well aware that they would not be able to escape from Stalingrad but in their letters to their families boasted that they were proud to "sacrifice themselves for the Führer".

Out of the nearly 91.000 German prisoners captured in the Battle of Stalingrad, only ± 5.000 returned. Weakened by disease, starvation and lack of medical care during the encirclement, they were sent on foot marches to prisoner camps and later to labour camps all over the Soviet Union. Some 35,000 were eventually sent on transports, of which 17.000 did not survive. Most died of wounds, disease, cold, overwork, mistreatment and malnutrition. Some were kept in the city to help rebuild it.

A handful of senior officers were taken to Moscow and used for propaganda purposes, and some of them joined the National Committee for a Free Germany. Some, including Paulus, signed anti-Hitler statements that were broadcast to German troops. Paulus testified for the prosecution during the Nuremberg Trials and assured families in Germany that those soldiers taken prisoner at Stalingrad were safe. He remained in the Soviet Union until 1952, then moved to Dresden in East Germany, where he spent the remainder of his days defending his actions at Stalingrad and was quoted as saying that Communism was the best hope for postwar Europe. General Walther von Seydlitz-Kurzbach offered to raise an anti-Hitler army from the Stalingrad survivors, but the Soviets did not accept. It was not until 1955 that the last of 6.000 survivors were repatriated (to West Germany).

Casualties

The calculation of casualties depends on what scope is given to the Battle of Stalingrad. The scope can vary from the fighting in the city and suburbs to the inclusion of almost all fighting on the southern wing of the Soviet–German front from the spring of 1942 to the end of the fighting in the city in the winter of 1943. Scholars have produced different estimates depending on their definition of the scope of the battle. The difference is comparing the city against the region. The Axis suffered 647.300 - 968.374 total casualties (killed, wounded or captured) among all branches of the German armed forces and its allies:

Approximately 285.000 in the 6th Army from 21 August to the end of the battle: 17.293 in the 4th Panzer Army from 21 August to 31 January; 55.260 in the Army Group Don from 1 December 1942 to the end of the battle (12.727 killed, 37.627 wounded and 4.906 missing) The combined German losses of 6th Army and 4th Panzer were over 300.000 men. If the losses of Army Group A, Army Group Don and other German units of Army Group B during the period 28 June 1942 to 2 February 1943 are included, German casualties were well over 600.000. Louis A. DiMarco estimated the German suffered 400.000 total casualties (killed, wounded or captured).

Around 235.000 German and allied troops in total, from all units, including Manstein's ill-fated relief force, were captured during the Battle of Stalingrad only around 5.000 returned to Germany after the war.