10 July - 31 October 1940

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain is the name given to the Second World War air campaign waged by the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) against the United Kingdom during the summer and autumn of 1940. The name is derived from a famous speech delivered by Prime Minister Winston Churchill in the House of Commons: " The Battle of France is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin."

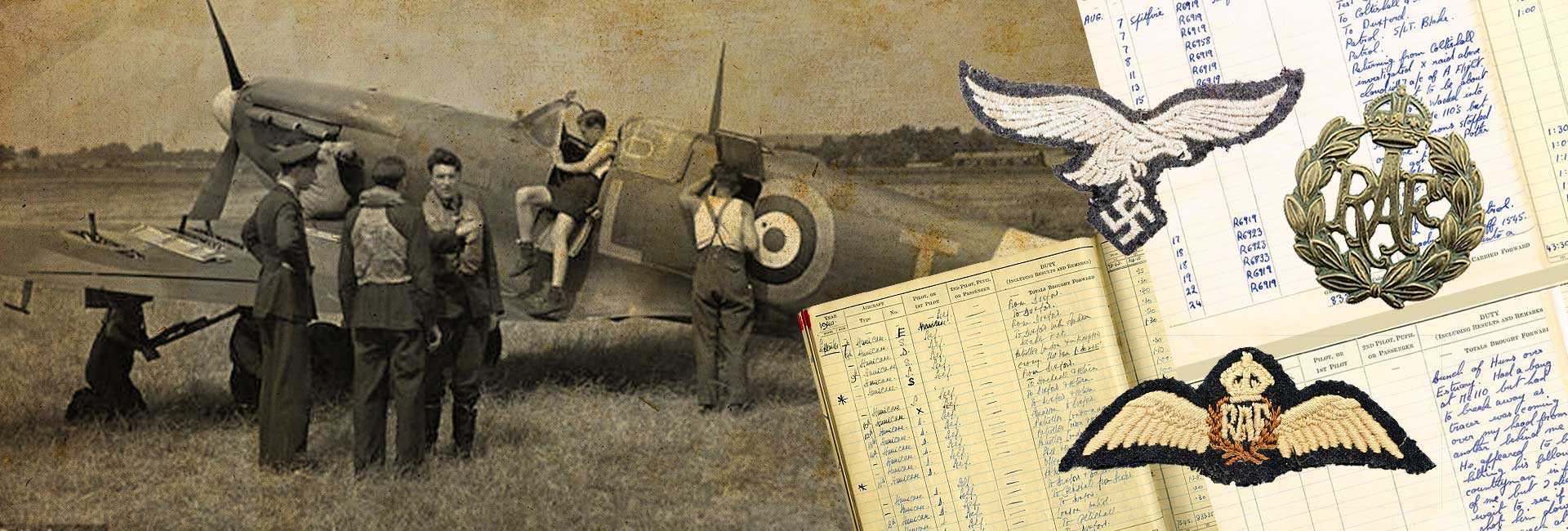

The Battle of Britain was the first major campaign to be fought entirely by air forces, and was also the largest and most sustained aerial bombing campaign to that date. The objective of the campaign was to gain air superiority over the Royal Air Force (RAF), especially Fighter Command. From July 1940, coastal shipping convoys and shipping centres, such as Portsmouth, were the main targets; one month later the Luftwaffe shifted its attacks to RAF airfields and infrastructure. As the battle progressed the Luftwaffe also targeted aircraft factories and ground infrastructure. Eventually the Luftwaffe resorted to attacking areas of political significance and using terror bombing strategy.

"Never was so much owed by so many to so few."

Speech of British prime minister Winston Churchill on 20 August 1940.

Royal Airforce

Luftwaffe

Battle specifications

Date of the battle

Duration of the battle

Reason for the battle

Location

Battle result

Allied casualties

-

Killed: 1542

-

Wounded: 422

-

Planes lost: 1744

Axis casualties

-

Killed: 2585

-

Wounded: 735

-

Planes lost: 1977

Commanders of the The Battle of Britain

Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding

Hermann Göring

The failure of Germany to achieve its objectives of destroying Britain's air defences, or forcing Britain to negotiate an armistice or an outright surrender, is considered its first major defeat and a crucial turning point in the Second World War. By preventing Germany from gaining air superiority, the battle ended the threat that Hitler would launch Operation Sea Lion, a proposed amphibious and airborne invasion of Britain.

The Germans launched some spectacular attacks against important British industries, but they could not destroy the British industrial potential, and made little systematic effort to do so. Hindsight does not disguise the fact the threat to Fighter Command was very real, and for the participants it seemed as if there was a narrow margin between victory and defeat. Nevertheless, even if the German attacks on the 11 Group airfields which guarded southeast England and the approaches to London had continued, the RAF could have withdrawn to the Midlands out of German fighter range and continued the battle from there. The victory was as much psychological as physical.

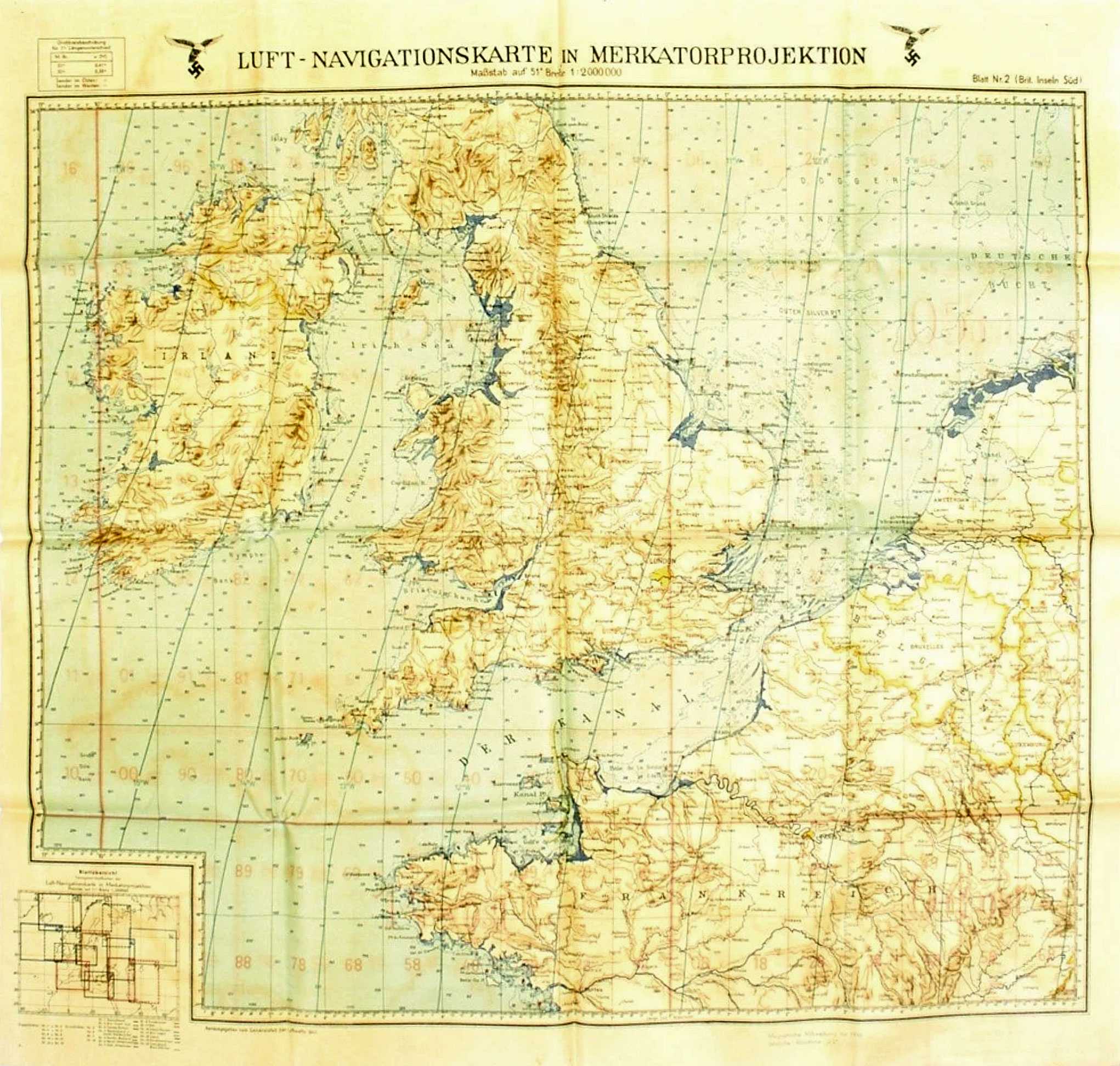

The high command's indecision over which aim to pursue was reflected in shifts in Luftwaffe strategy. Their Air War doctrine of concentrated close air support of the army at the battlefront succeeded in the blitzkrieg offensives against Poland, Denmark and Norway, the Low Countries and France, but incurred significant losses. The Luftwaffe now had to establish or restore bases in the conquered territories, and rebuild their strength. In June 1940 they began regular armed reconnaissance flights and sporadic Störangriffe, nuisance raids of one or a few bombers, both day and night. These gave crews practice in navigation and avoiding air defences, and set off air raid alarms which disturbed civilian morale. Similar nuisance raids continued throughout the battle, into late 1940. Scattered naval mine-laying sorties began at the outset, and increased gradually over the battle period.

Göring's operational directive of 30 June ordered destruction of the RAF as a whole, including the aircraft industry, with the aims of ending RAF bombing raids on Germany and facilitating attacks on ports and storage in the Luftwaffe blockade of Britain. Attacks on Channel shipping in the Kanalkampf began on 4 July, and were formalised on 11 July in an order by Hans Jeschonnek which added the arms industry as a target.

On 16 July Directive No. 16 ordered preparations for Operation Sea Lion, and on the next day the Luftwaffe was ordered to stand by in full readiness. Göring met his air fleet commanders, and on 24 July issued "Tasks and Goals" of gaining air supremacy, protecting the army and navy if invasion went ahead, and attacking the Royal Navy's ships as well as continuing the blockade. Once the RAF had been defeated, Luftwaffe bombers were to move forward beyond London without the need for fighter escort, destroying military and economic targets.

Writes Alfred Price:

The truth of the matter, borne out by the events of 18 August is more prosaic: neither by attacking the airfields, nor by attacking London, was the Luftwaffe likely to destroy Fighter Command. Given the size of the British fighter force and the general high quality of its equipment, training and morale, the Luftwaffe could have achieved no more than a Pyrrhic victory. During the action on 18 August it had cost the Luftwaffe five trained aircrew killed, wounded or taken prisoner, for each British fighter pilot killed or wounded; the ratio was similar on other days in the battle. And this ratio of 5:1 was very close to that between the number of German aircrew involved in the battle and those in Fighter Command. In other words the two sides were suffering almost the same losses in trained aircrew, in proportion to their overall strengths. In the Battle of Britain, for the first time during the Second World War, the German war machine had set itself a major task which it patently failed to achieve, and so demonstrated that it was not invincible. In stiffening the resolve of those determined to resist Hitler the battle was an important turning point in the conflict.

Aftermath

The Battle of Britain marked the first major defeat of Germany's military forces, with air superiority seen as the key to victory. Pre-war theories had led to exaggerated fears of strategic bombing, and UK public opinion was buoyed by coming through the ordeal. For the RAF, Fighter Command had achieved a great victory in successfully carrying out Sir Thomas Inskip's 1937 air policy of preventing the Germans from knocking Britain out of the war.

The battle also significantly shifted American opinion. During the battle, many Americans accepted the view promoted by Joseph Kennedy, the American ambassador in London, who believed that the United Kingdom could not survive. Roosevelt wanted a second opinion, and sent William "Wild Bill" Donovan on a brief visit to the UK he became convinced the UK would survive and should be supported in every possible way. Before the end of the year, American journalist Ralph Ingersoll, after returning from Britain, published a book concluding that "Adolf Hitler met his first defeat in eight years" in what might "go down in history as a battle as important as Waterloo or Gettysburg". The turning point was when the Germans reduced the intensity of the Blitz after 15 September. According to Ingersoll, "majority of responsible British officers who fought through this battle believe that if Hitler and Göring had had the courage and the resources to lose 200 planes a day for the next five days, nothing could have saved London"; instead, "morale in combat is definitely broken, and the RAF has been gaining in strength each week."

Both sides in the battle made exaggerated claims of numbers of enemy aircraft shot down. In general, claims were two to three times the actual numbers. Postwar analysis of records has shown that between July and September, the RAF claimed 2.698 kills, while the Luftwaffe fighters claimed 3.198 RAF aircraft downed. Total losses, and start and end dates for recorded losses, vary for both sides. Luftwaffe losses from 10 July to 30 October 1940 total 1.977 aircraft, including 243 twin- and 569 single-engined fighters, 822 bombers and 343 non-combat types. In the same period, RAF Fighter Command aircraft losses number 1.087, including 53 twin-engined fighters. To the RAF figure should be added 376 Bomber Command and 148 Coastal Command aircraft lost conducting bombing, mining, and reconnaissance operations in defence of the country.

There is a consensus among historians that the Luftwaffe were unable to crush the RAF. Stephen Bungay described Dowding and Park's strategy of choosing when to engage the enemy whilst maintaining a coherent force as vindicated; their leadership, and the subsequent debates about strategy and tactics, had created enmity among RAF senior commanders and both were sacked from their posts in the immediate aftermath of the battle. All things considered, the RAF proved to be a robust and capable organisation which was to use all the modern resources available to it to the maximum advantage.

The Germans launched some spectacular attacks against important British industries, but they could not destroy the British industrial potential, and made little systematic effort to do so. Hindsight does not disguise the fact the threat to Fighter Command was very real, and for the participants it seemed as if there was a narrow margin between victory and defeat. Nevertheless, even if the German attacks on the 11 Group airfields which guarded southeast England and the approaches to London had continued, the RAF could have withdrawn to the Midlands out of German fighter range and continued the battle from there. The victory was as much psychological as physical. Writes

Casualties

The British victory in the Battle of Britain was achieved at a heavy cost. Total British civilian losses from July to December 1940 were 23.002 dead and 32.138 wounded, with one of the largest single raids on 19 December 1940, in which almost 3.000 civilians died. With the culmination of the concentrated daylight raids, Britain was able to rebuild its military forces and establish itself as an Allied stronghold, later serving as a base from which the Liberation of Western Europe was launched.